|

|

|

|

|

"I Am What I Remember."

Welcome to my weblog. My mother Libby D'Ignazio has Alzheimer's Disease. I love my mom as much as I love any person in

the world. I know she loves me. Having her slowly drift away from me and not know me is something I can't bear.

I will use this weblog (or "blog") as a public diary. I will tell you what I learn, experience and feel as I go through

my days as the son of a person with Alzheimer's. I hope that this journal will help others as they follow the same path I

am following.

-- Fred D'Ignazio (Fall 2005) |

|

Please send me your comments by using the form on the "Contact Us" page. Let me know if you want me to post your comment in the blog. Also, tell me if you want your email address listed.

This blog appears each day with the newest article on the top and the oldest article stored in the blog's

monthly archives. In effect, it reads backwards!

To read the blogs in chronological order or to find a particular blog, click on Blog Articles.

For a quick introduction to the blog, take a look at:

"The Long and Winding Road" is the first article in the blog. It appeared on Monday, October 24, 2005.

|

|

|

|

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

My Mom the Card Shark

My mom is an excellent bridge player. She also has Alzheimer's Disease.

How can Mom have Alzheimer's and play cards? Doesn't card playing require memory skills?

Mom's memory is fading. For example, as she was headed out the door yesterday to play bridge at my mother-in-law Doris

Letts' house, Mom turned to Dad and said: "Now where am I going again?"

Once she got to Doris's house, Mom was fine. Here is the email that Doris sent me this morning:

It went great. She was just like I always knew her -- sharp at the cards -- and seemed to enjoy the get together .....

I called Mom this morning and she told me she had fun at Doris's. "I worried that I might not remember things,"

she told me. "But once we started playing, I was fine. I had a good time."

PLAYING CARDS WITH ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

The fact that Mom can play cards is good. The Alzheimer's Association publishes a list of the seven warning signs that signal the onset of Alzheimer's Disease. One of these signs is:

Forgetting how to cook, or how to make repairs, or how to play cards — activities that were previously done with

ease and regularity.

I'd like to see Mom playing cards more often. It's not proven that playing bridge will slow the progress of Alzheimer's

Disease, but it can't hurt. Mom obviously has considerable brainpower left for her to be "sharp at the cards." Perhaps by

exercising her brain she can keep the working part of her brain disease-free for a longer time.

Mental activity (like playing cards) has been shown, in study after study, to lower the risk of Alzheimer's Disease

for people who are dementia-free. It might also be a good activity for people, like my mother, who are in the early stages

of the disease.

USE IT OR LOSE IT

Studies have found that people who are dementia-free have a lower chance of getting Alzheimer's and other forms

of dementia if they keep active mentally. For example, in a 2002 study sponsored by the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center in Chicago:

The study followed over 700 dementia-free participants age 65 and older for an average of 4.5 years from their

initial assessments. At baseline and then yearly, some 21 cognitive tests were administered to assess various aspects of memory,

language, attention, and spatial ability. At the initial evaluations, participants also were asked about time typically spent

in seven common activities that significantly involve information processing - viewing television; listening to the radio;

reading newspapers or magazines; reading books; playing games such as cards, checkers, crosswords, or other puzzles; and going to museums.

The study found that the frequency of activity was related to the frequency of contracting Alzheimer's Disease.

For every one point increase in a person's activity score, the risk of developing Alzheimer's Disease dropped by 33 percent.

On the average, compared to someone who did the fewest mental activities, the risk of the disease was reduced by 47 percent

for those who regularly had the most activities.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Old Age Is Not for Sissies

On WHYY-Philadelphia's Voices in the Family radio show, host Dan Gottlieb recently had guests who discussed

the impact of depression on an older person's health. (Click here to listen to the 52-minute program on RealPlayer.)

Dan began the program by citing Art Linkletter's famous book entitled Old Age Is Not for Sissies. He commented on the data that almost 50% of residents of nursing homes are diagnosed as depressed; while only

29% of seniors, in general, have depression. According to guest Dr. Ira Katz, geriatric psychiatrist at the University of

Pennsylvania, depression is not the fault of the nursing homes. Instead, he said, depression and dementia disorders (chiefly

Alzheimer's) are the primary reasons that seniors are put into nursing homes.

According to Dan, the current generation of seniors shows a mental toughness that earlier generations didn't have. The

cause for this resilience may be related to the challenging life experiences the seniors have had, including the Great Depression,

World War II, and the threat of nuclear holocaust.

Rabbi Zalman Schachter, author of "From Aging to Saging," offered the insight that aging without extended consciousness

is like dying longer. His point was that old age is commonly seen as a time when our minds slow down, and when the world seems

to speed up. Cell phones, the Internet, 400-channel TVs, voice mail, answering machines -- all are hazards and hurdles

that seniors must learn how to navigate. If not, they risk falling behind, cursing and spluttering as they slam

down the telephone and shut off contacts with an increasingly mystifying outside world.

Rabbi Schachter's idea is to use new brain research that shows that for most seniors, almost all of their 100 billion

neurons are still firing. There is no need for older people to barricade the doors, raise the shields and go into siege

mentality. But what alternative do they have?

WHAT IS MY PLACE IN THE WORLD?

The process of "extending consciousness" and renewing a commitment to life begins with asking oneself the question:

"What is my place in the world?"

According to the host, Dan Gottlieb, when we make new social associations we "put our ego to sleep" and we find a new

meaning for our lives in the lives of those around us. This extends consciousness beyond our own bodies and situation to the

lives of others -- their welfare, their happiness, and their well-being. It is an extension of concern. When we extend

our concern to the well-being of others we approach life rather than resigning ourselves to a quiet dying.

WE ARE LIKE SEA GLASS WITH SOFTENED EDGES

When we look at ourselves right this moment, how do we see ourselves? Do we have sharp edges or rounded edges? Apparently

people who age evolve into one of these two types.

Dan Gottlieb likened aging to glass that emerges from the sea after long periods of being rubbed and rounded by ocean

sand. Early on in life, he said, we have sharp edges. But, like sea glass, our edges become rounded as we crash into life

experiences, bumping and grazing against all around us. The outcome, if we are lucky, is that in old age we at last become

comfortable in our own skins.

Monday, November 28, 2005

How Can I Understand What You Are Going Through?

I've been following the story of Tom DeBaggio, a 56-year-old writer, commentator, and herb grower, who came down with

early-onset Alzheimer's Disease in 1998. Now 63, Tom is still alive, although his mental abilities have dropped precipitously

in the last year. He no longer writes. He can't read. And, worst of all, his will to go on living has weakened.

On May 19th and May 20th 2005, NPR's All Things Considered interviewed Tom and his wife Joyce at their

herb farm in Chantilly, Virginia. The program ran in two parts: In Part One, the interviewer concentrated on Tom. In Part Two, we hear from Joyce what has been like to be a caregiver of a person with Alzheimer's.

Tom and Joyce's plight reminds me of my mom and dad. Dad is Mom's primary caregiver. I've written in earlier blog postings

about the intimate dance that a caregiver does with the loved one they are caring for. The two of them are bound

together, for better or worse, trying to see the process through. On the way, the individual steps can exhaust both of them.

Here is an excerpt from Tom and Joyce's interview:

Joyce: "He forgets immediately what was said before. And it gets very frustrating because I will continue to repeat what

I said, and as I repeat it, I get louder, for some reason. And then he thinks I'm shouting at him." (Laughing.) "And

then he gets angry and upset because he thinks I'm shouting at him. And then we have to go back, and we start again. And that

gets very frustrating."

Joyce (continued): "I asked him once if he could understand how frustrating it gets for me, and he said no, he couldn't."

NPR Interviewer: "You don't see that, Tom?"

Tom: "What?"

NPR Interviewer: "The frustration for her?"

Tom: "I don't even think of that, because I don't know what she is."

Joyce: "What do you mean?"

Tom: "We're different. That's all."

Interviewer: "So her experience of your disease is alien to you?"

Tom: "Yeah. She can't possibly know what I'm going through. But I don't know it either, because I can't remember."

Sunday, November 27, 2005

"I Can't Remember Yesterday."

Ginny Alyanakian, Mom's best friend, died just three nights ago, on Thanksgiving evening.

On Friday morning, the day after Thanksgiving, I called my mom from North Carolina. We had an emotional conversation on the

phone. (See my blog.)

All day long, on Friday, I worried about Mom's state of mind. Late in the day I called her. She was out at hers and Dad's

farm in Oxford, Pennsylvania. When she answered the phone her voice was happy and energetic. "We've had a wonderful day!"

she exclaimed. "Joe and Naomi Tercha took us on a drive today, and we saw so many things. We've watched football on TV, and

now we're going to Owsley's for dinner. It was a great day."

What a relief. After only one day, Ginny's death was behind her--at least temporarily. Mom's quick recovery reminded

me of Tom DeBaggio's comments in an interview for National Public Radio:

Tomorrow I won't remember this [interview]. I can't remember yesterday. And unless it's something exceptional, such as

this, I might remember it for a couple of days, but I just have no memory of yesterday at all.

Is that distressing?

"Actually, no. It relieves me of a whole lot of things. You know, when you don't remember what you did yesterday, you can't

feel bad about it or good about it, you know? It's just not there. And you're really living in the moment."

"I Get Angry If a Chair Is Moved in the House."

Living in the moment is good, but it makes one's moments fragile and often precarious. If you can't take yesterday

with you, you greet each new morning fresh, with no memory where you left your life the night before.

Mom fights her memory loss by keeping herself oriented at the level of tiny details. When I visited her I noticed

how she flies around the apartment where she and Dad live, turning on lights, pulling up blinds, and pushing in chairs. I

noticed that she didn't neaten up her entire living space, just certain items. I think these are her "orienting" items that

she focuses on. When those items are okay, then Mom is okay. If those items are out of place, then Mom feels disoriented.

She explodes in frustration, crying out, "Who put this here?"

I've also noticed how cautious Mom is about going anywhere without my Dad. Obviously, she is very dependent on

my dad emotionally and mentally. They have been married for over 58 years. But I think my dad is my mom's "mobile orienter,"

her anchor. When Dad is with her, Mom feels grounded.

My two brothers and my sister have tried to get Mom to socialize more, to get involved in volunteer activities,

and to look for fresh interests to engage her mind. But, mostly, they have failed to interest Mom. She is more comfortable

keeping house, watching TV and reading the newspaper, and staying very close to my father.

Tom DeBaggio describes this same feeling in When It Gets Dark, his book on Alzheimer's Disease:

The real reason we haven't gone anywhere is that I am afraid of getting lost. I need the familiar around me to

give me comfort and stability. I am at such a tender point in life now that I worry when I head out for the grocery store

five blocks away. I get angry if a chair is moved in the house.

Saturday, November 26, 2005

Mom & Dad's Inner Circle

Kurt Vonnegut in his novel Cat's Cradle creates a religion that he calls Bokononism, founded by the fictitious black Episcopalian Lionel Boyd Johnson from Tobago.

One of the key terms in Bokononism is the karass -- a team of people who do God's Will without knowing it. A specialized

form of karass is the duprass. A duprass is a karass composed of only two persons. According to Vonnegut, a duprass

is:

a valuable instrument for gaining and developing, in the privacy of an interminable love affair, insights that are queer

but true. ... [A duprass is] a sweetly conceited establishment.

The members of a duprass are so intricately bound together that, according to Vonnegut, they "die within a week

of each other."

I believe that Mom and Dad form a duprass -- an inner circle that admits no other members. Dad described the

development of this special relationship in the video he narrated for Mom's 80th birthday. He said that at first what attracted

them to each other was passion. But after many years their passion evolved into a deep love. "Some people have love," said

Dad, "and some don't. We happen to have it."

When I was in Pennsylvania last week I lived in the back room of Mom and Dad's apartment. I watched TV with them,

ate meals with them, chatted with them, did errands with them, and helped them do household chores. I felt very welcomed by

them. I knew they appreciated my being there.

But I always felt a little bit removed, a little displaced from their inner circle. It wasn't a bad feeling.

It was interesting to observe. When one spoke, the other one always answered. On the other hand, often when I asked a question

or made a comment, I was met with silence. I felt a teeny bit invisible.

In Mom and Dad's duprass -- their interminable love affair, their sweetly conceited establishment --

they only have eyes for each other. And ears, too.

Friday, November 25, 2005

Good-Bye, Mike. Good-Bye, Ginny.

This is a sad day for me and my family. Right now, as I write this blog entry, my mom's family in Kentucky is holding

a memorial service for my cousin, Mike McComas, who passed away October 30th. And this morning my sister-in-law, Teri D'Ignazio,

called and told me that my mom's best friend, Ginny Alyanakian, died last night.

I wrote about Mike in my November 2nd blog, just three days after he died. Mike was a smart guy -- a Phi Beta Kappa graduate from the University of Kentucky, an archaeologist,

a systems analyst, and a dendrochronologist who mapped cone-pine rings to determine historical weather patterns. (See his

obituary here.) But he moved to Tucson, Arizona, decades ago, and his brothers and parents in Kentucky and my family in Pennsylvania all

lost touch with him.

What I've discovered since Mike died is that distance in time and space don't eliminate the grief you feel when someone

in your family passes away.

This morning Teri D'Ignazio called me to tell me that Ginny Alyanakian had passed away last night, in her sleep, on Thanksgiving

evening.

I had just visited Ginny on Monday of this week with my sister-in-law Nancy Flandreau D'Ignazio. Nancy sent me a voice

message after she heard about Ginny's death. Her feelings mirrored mine. We are both a bit in shock. On Monday night Ginny

had looked animated and very much alive. She told us that she planned to be driving again, just like her old feisty self.

And now, suddenly, she was gone.

I called my mom right away. I tried hard not to be emotional, but I wasn't capable of keeping the tears and the sadness

out of my voice. "I'm 56 years old," I told my mom. "And I've known Ginny, and she's known me for all fifty-six years. She

was your oldest friend, and she was mine, too."

Typical of my relationship with my mother, I called to offer her comfort, but she ended the conversation comforting me.

"Don't be sad," she told me. "Thank you for being there with me. When I think of Ginny, now, I'll think of you."

Mom's voice trembled. And it troubled me. On one hand, I was elated to hear that Mom is connected to life so that Ginny's

death affected her. On the other hand, I didn't want Mom to really be aware that she had lost her best friend.

Just the other night I asked my mom and dad, at my dad's restaurant, who was their best friend. Dad said, "Sal." Sal

Melchior is an old buddy of my dad's. And, of course, Mom answered, "Ginny."

Thursday, November 24, 2005

The Purpose of This Blog

While I was in Pennsylvania visiting my parents I heard from my wife that one of my mom's friends had read the blog and

was alarmed by its contents. I called the friend and asked her reaction to the blog. She felt that I was over-dramatizing

my mother's condition, and she was worried that it was affecting me emotionally.

In a way, this is a good reaction. I'm writing this blog so others can read it and react. I don't expect everyone

will see things my way. And I hope to hear from anyone who has additional information or another opinion about issues I've

raised.

As I say in the introduction to the blog, "I will tell you my perspective." I understand that my perspective is subjective

and not necessarily the truth. But I felt it would be more of a service to everyone else if I was honest and frank about what

I see and what I feel. You judge if I'm right.

Also, if you have read several entries in my blog, you'll see that it is a "hybrid blog" -- both a diary and a research

blog with lots of links to other sites on the web where you can get expert information about Alzheimer's Disease. Since it

is a research blog, I don't always write about my mother. I'm trying to understand the bigger picture, so I write about other

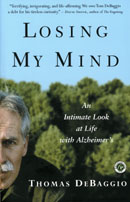

people, other families, and other situations. For example, I've written about Tom DeBaggio, the gentleman in Virginia who came down with early-onset Alzheimer's Disease. Mr. DeBaggio is still alive, six years after

contracting Alzheimer's. He has written a new book, When It Gets Dark: An Enlightened Reflection on Life with Alzheimer's. And he appears in two 2005 National Public Radio broadcasts, along with his wife Joyce in a story entitled, Tom DeBaggio's Alzheimer's Journey Continues.

I've also written about Jeff Stewart and his family in North Carolina. Like Tom DeBaggio, Jeff Stewart has early-onset Alzheimer's Disease.

Why have I written about these other families? Partly because they present heroic examples of families coping with the

tragedy of this disease. In addition, I write about them because Alzheimer's is on my mind, too. I dwell on the disease.

How can I not? My mother is suffering from its effects, and I worry daily that I may get it, too. Maybe I'll get it sooner.

Maybe not. But it does bother me.

Our family friend said that my mom is coping well with Alzheimer's and is still largely the person she has been for all

of her 81 years. This is true -- and not true. My mom is an extraordinary individual. With or without Alzheimer's, she is

still remarkable. But it is easy to see after spending a day or two with her how her life has been affected by this disease.

I think this blog is on the right track. My father said that Mom might not recognize any of us in another year. So I'm

focusing my attention on Mom right now. I want to learn as much as I can and I want to help my dad and be with mom as much

as I can. I'm so blessed to have Elizabeth McComas D'Ignazio as my mother. It's important that I remember that blessing every

day that she is still part of my life.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

"She Just Gained Another Five I.Q. Points"

I've recently returned from a five-day visit with my mom and dad in Pennsylvania. My folks just celebrated their

58th wedding anniversary; they have been married since 1947. During this time they have fought with each other, struggled

together, achieved great success together, and forged an enduring love. They are a remarkable couple.

When I travel up from North Carolina to visit them I stay in the back bedroom of their tiny, first-floor apartment. I

love being with them and sharing in their daily routines. It also gives some respite to my father. After the onset of Mom's

Alzheimer's disease, he has been her primary caregiver (see my blog), and this has worn him pretty thin. After all, he is 88 years old. He does a great job looking after my mom, but he

is hampered by his heart condition and his acute arthritis, and he is on medication. My mom has suffered a significant

loss in her memory, but she is physically as robust as ever. Keeping up with my mom wears out my dad.

My mom's Alzheimer's Disease causes her to forget many of the details she needs to get through her day. Nothing

is obvious to my mom any more. So she is always asking my dad to help her do things and find things. When she can't figure

something out, or if dad isn't at hand, she immediately gets angry and frustrated. She lashes out, and usually my dad is her

target.

Most of the time Dad is extraordinarily patient with Mom. He endures her bad tempers and her explosive outbursts with

good humor. He responds with quiet answers to her barked questions and outcry. But sometimes he loses his patience and returns

to the kind of needling he used to do when they were younger and before Mom came down with Alzheimer's.

When he does this, I freeze. I look over at Mom, and she has that tough, bulldog look on her face. Her lips get thin,

her eyes narrow, and I fear she is going to jump on him and throttle him.

Of course she doesn't do anything. But her look is menacing. And does my dad back off? Instead he keeps stirring the

pot, saying things that I know are bound to heat up her Scotch-Irish temper to the boiling point.

I wait for the explosion. But after a few angry exchanges wth Dad, Mom backs off.

When I was at home this time I asked Dad why he does this. Is it because he can't take it any more?

His answer surprised me. "I do it," he told me, "to bring her back. I watch her sinking deeper and deeper inside herself.

She gets that glazed look on her face, and I don't like that. When I get her temper going, she bounces back."

After Dad told me this, I watched the two of them even more carefully. Sure enough. Every time they had a spat, Mom would

become more animated, more aware of her surroundings, and more like her old self. It was amazing. The effect was temporary

but significant.

"Each time I stir your mother up," my dad said, "it's like she gains another five I.Q. points. You have a very smart

mother. And we get to see a little bit of how smart she is each time I rile her up. You have to interact with her. You can't

let her wander off on her own. Keep her body moving, and keep her mind engaged, even if it's to fuss at me. I can take it."

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

"She Is The First Person Who Recognized Me"

Two days ago, on Sunday, I went with my mom to her church in Media. Mom has attended this church for over fifty years.

(See my blog.) The service was beautiful. Before and during the service Mom kept leaning over and whispering to me. She reminded me that

she has worked in almost every part of the church doing volunteer activities. She reminded me that she has been a member of

her church since the 1940s. Yet no one knew her. Not a single person came up to her and greeted her during the service.

It wasn't until the end. As we were leaving a woman approached Mom and greeted her and said she was happy to see Mom.

Mom beamed. After the woman left, she said, "She is the first person here who recognized me. I've been coming here for

more than 50 years, and she is the first one who knew me."

The truth is that no one did know mom. At 81 Mom has outlasted most of her friends and contemporaries. If they are still

alive, they are not attending church services.

This is a sad corollary of longevity--i.e., loneliness. If you live long enough, your friends all pass away. And, after

awhile, no one knows you. You, who were one of the first people on the scene, are treated as if you are a newcomer.

Friday, November 18, 2005

"Things Are Just Moving Faster."

This is the advice my mom's friend, Phyl Di Paola, had for my mom at lunch yesterday. Phyl, like the rest of us, is conscious

of mom's loss of memory. But Phyl is also sensitive to the anxiety mom feels when she can't remember. She was trying

to reassure Mom that at least part of what she is experiencing is due to the faster pace of life, and not to mom's own forgetfulness.

My mom thanked her friend with considerable emotion, and I knew Phyl had made mom feel better.

I'm up here in Pennsylvania, visiting with my mom and dad for five days. What I've observed, so far, has been very ambiguous.

I've watched mom carefully ever since I arrived yesterday morning.

When I walked in the front door, laden with suitcases, Mom looked thrilled to see me. She was well groomed and dressed

stylishly, as always, with a blouse, skirt, and jacket, all in autumnal colors. She had prepared my room for my arrival. She

had bought fresh flowers to greet me.

The moment after I arrived, Mom rushed me out the door. She drove me around town doing errands -- getting a newspaper,

taking clothes to the cleaners. She was chatty and drove well. She seemed oriented at all times, as she weaved through streets

full of traffic and road construction.

At the cleaners she was sharp: she remembered the clothes she had brought earlier in the week, and she was assertive,

yet friendly, with the lady behind the counter.

After we returned back to mom and dad's apartment, Mom had a moment of anxiety when she couldn't find her purse. She

became flustered and rushed around the apartment, looking for the purse and muttering to herself.

Later in the day, my father met with me and my two brothers and sister about caregiving arrangements he was making for

himself and mom. We were talking about identity bracelets, and how he and Mom both needed ID bracelets in case of emergency.

Dad is almost 88, he has high blood pressure and has been warned that he might suffer a stroke at any time. Mom has been

diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer's Disease. In case he passed out or Mom became disoriented, a bracelet would tell people

who they were, whom to call, and give some basic data about their blood type and health conditions.

My dad's accountant, who is a close family advisor said, "Do you know what is the first item that women with Alzheimer's

misplace? It is their purse. They lose their purse. Then if they can't identify themselves, without an ID bracelet, there

is no telling who they are or how to care for them. They become a 'Jane Doe.'"

Thursday, November 17, 2005

"We Have Something Better. We Have Each Other."

This was what my mom's friend said to us as we sat with her over lunch today at my dad's restaurant in Media, PA.

My mom, Libby D'Ignazio, and her friend, Phyl Di Paola, have been friends since the early 1950s.

"But we almost missed becoming friends," said Phyl. "The first time we came here, the restaurant was just a one-room

bar. I remember walking out this door over here (she points to the door behind my mother). My husband Ray followed me out

on the street calling, "Phyl! Phyl! What's wrong?" I was in a huff, and I said. "I'm never going back there again."

"Why did you say that?" I asked.

"I don't remember," Phyl said. "Shortly after that dinner, your mom and I met, and your dad hired Ray to be his architect

to build the restaurant. We've been friends ever since. And I've been coming here for more than fifty years."

Over and over, our conversation returned to memories. The women told stories to each other, and laughed and reminisced.

I felt we were in 2005, then in in 1955, and then somewhere in between.

Memory is a mental stabilizer and without it the mind becomes chaotic and unstructured, allowing 1999 and 1940 to merge.

My dad sat down with us and he, too, began to reminisce. "Remember the Depression?" he said. "It was a tough

time, but a good time, too. That's when we learned the greatest lesson--how to survive. I remember working at Superior Market,

up on State Street. I worked all week long, just so I could take home a turkey on Thanksgiving Day. I couldn't believe I'd

done it. The turkey was worth over two dollars."

Mom responded with a memory of her own: "My lesson was patience," she said. "You worked so hard at the restaurant

that I barely saw you. For the first fifteen years of our marriage, we saw each other only enough to have kids."

"We used to have a lot of energy in those days, didn't we," said Phyl.

"We did," agreed my mom.

"That's okay," said Phyl. "Now we have something better. We have our memories. And we have each other."

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Losing My Mind

I've always been a bit absent-minded and forgetful. So when I learned that my Mom has Alzheimer's Disease I felt more

than moderate anxiety. I wondered: Will I develop Alzheimer's like my Mom? If so, when will I first notice it? And even

worse: do I have the gene markers for early-onset Alzheimer's? (See yesterday's blog post.)

I know that I can't "catch" Alzheimer's Disease from my mom. (See my blog post.) But now I see every bit of random forgetfulness as another sign of early-onset Alzheimer's.

A book that puts my worries into proper perspective is Thomas DeBaggio's Losing My Mind. Tom's first symptoms of Alzheimer's Disease, forgetfulness and inability to concentrate, began when he was just

56 years old -- exactly my age.

My symptoms are lightweight compared to Tom's symptoms. When he first receives his Alzheimer's diagnosis from the neurologist,

he writes:

A new world greets me every morning now. I will never see myself or the world the same way. I must cling to optimism

and avoid depression, but today I am so shattered I can hardly hold a word, phrase, or sentence long enough to acknowledge

it and put it on paper. It is as if I received a death sentence and I have to begin a circumscribed life in a prison of fear.

I see myself differently, almost as if a death ray penetrated me. I look in a mirror and discover I am crying.

The book is a brutally honest, unblinking account of what the author sees, feels, and thinks as he sinks into

Alzheimer's Disease. He is an excellent writer and he weaves accounts of his trips to the doctors with historical recollections

of his early life, and he inserts startling, stream of consciousness passages like the one above. Yet the book is also uplifting

as you see the man's naked spirit exposed. He is a good man and he chooses writing this book over taking experimental drugs

so that he can act as an explorer of the disease and report back to the rest of us what it is like.

His sad and tormented passages are balanced with comments like: "Now is the last best time" and "What better

way to die than to celebrate life!"

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Early-Onset Alzheimer's Disease

Last year I was at one of my church's Tuesday Morning Prayer Breakfasts. I was seated to the left of a nice looking fellow

who appeared to be about 40 or 45. He introduced himself as Jeff. He seemed friendly, but there was something a little odd

about him that I couldn't pin down. Being the overly sensitive person I am I took it personally and wondered if he was mad

at me, or if I had offended him. When I talked to him about my family, he seemed to be tuning out, as if he thought what I

said wasn't important. What was his problem? He and I had known each other ten minutes. How could he be mad at me?

Later, after the breakfast was over, I talked with one of my church buddies, Scott Rose. I had noticed that he and Jeff

were friends. Scott told me, "He's not mad at you, Fred. Far from it. Jeff's not mad at anyone. What Jeff's got is early-onset

Alzheimer's Disease."

EARLY-STAGE ALZHEIMER'S vs. EARLY-ONSET ALZHEIMER'S

Early-stage Alzheimer's Disease is the first point when tests show that an individual is ill. Most people do not

get Alzheimer's Disease before the age of 65. If someone does get Alzheimer's before the age of 65 it is called early-onset

Alzheimer's. According to the Alzheimer's Association:

Early-onset individuals may be employed or have children still living at home. Issues facing families include ensuring

financial security, obtaining benefits and helping children cope with the disease.

Approximately 6%-10% of persons with Alzheimer's have the early-onset form of the disease.

CAUSES OF EARLY-ONSET ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

Here are some of the major causes of early-onset Alzheimer's Disease:

-

Inherited genetic defects in chromosomes 1, 14 or 21. This defect is associated with the brain's production of betyl-amyloid

which is related to the fatty amyloid deposits that are found, postmortem, in the brains of all Alzheimer's sufferers.

-

Down's Syndrome is caused by a defect in chromosome 21. People with Down's Syndrome have an increased risk of contracting

Alzheimer's.

JEFF AND HIS FAMILY

Jeff and his family are profiled in an article in Triangle Senior Living's Alzheimer's Guide. (You can request a free

copy of the guide by clicking here.)

Jeff has a wife, Judy, and two daughters, MacKenzie, 13, and Jenna, 11. According to the guide, the whole family is coping

with Jeff's Alzheimer's as well as can be expected, but the daughters "have had to grow up much faster than other kids their

age." Judy says, "There are so many aspects that are beyond overwhelming."

According to the guide:

Judy began noticing a decline in Jeff shortly after his mother died of Alzheimer's in April 2002. The couple was fighting

more often, he was frequently tired, he even ran a red light. Then she found out he had been terminated from his job, in March

2003. That was the catalyst that got them to the doctor. After seeing five doctors in five weeks, Jeff finally received his

diagnosis from Dr. Donald Schmechel at Duke.

Judy is a self-sufficient person, but she realized that Jeff's disease created more problems than one person

could handle. "You think you've got everything done, then 20,000 other things come up," she admits.

Fortunately Judy did seek help -- from their friends, their church, and from the local chapter of the Alzheimer's Association. The chapter helped Judy quickly find expert physicians, family counseling and a day care facility for Jeff.

Jeff's disease kept progressing until Judy had to make the difficult decision to put Jeff into an assisted living

facility with a special care unit for people with dementia. "Who can imagine being 42 and looking for a nursing home for your

husband?" she confides.

The family continues to grapple with each stage of the disease as Jeff's condition worsens:

There are no easy answers here, no happy endings. Judy is in the unenviable position very familiar to those whose loved

ones have dementia. She has started the grieving process of losing Jeff, while still having a husband.

She realizes she has to start thinking about death. Maybe it will be one year, maybe five--she doesn't know. The hardest

thing to deal with these days is Jeff's continual decline. "The challenge of every day is watching him change," she says.

Monday, November 14, 2005

Memories of Mom -- Preparing the Lord's Supper

Mom has been a member of the Altar Guild of her church for 56 years. (Note to self: I'm 56! I'm

wondering if there is a connection between my birth and Mom deciding she needed to leave home and start volunteering at her

church.)

On countless Saturdays for the past half century my mom could be found either at Christ Church in Media, PA, or at St.

John's by the Sea in Avalon, New Jersey. She wasn't giving sermons or counseling church members. She was working quietly behind

the scenes preparing the church altar for Sunday service.

As president of the two churches' altar guilds her job was one of those dozens of church chores that are noticed only

if they are left undone. Each Saturday afternoon she showed up at church and prepared for the next day's communion service.

She brought church linens that she had washed at home. She straightened the altar and arranged the fresh linens. She carefully

set up the communion wafers, wine and water atop the altar. She hunted down collection plates and church candles and arranged

them on the altar.

Why has she done this routine for 56 years? I called her yesterday on the phone and asked her this question. Her answer: "I

do it because it makes me feel good. I like going to church when it is all quiet. I like moving around quietly, helping prepare

for Sunday's service. I think of it as my ministry."

When the service is over Mom goes back to the altar. She cleans the altar and puts everything away. Then she takes

the linens home to launder them for the next week.

Mom has been doing this job conscientiously since I was born. Maybe someone asked her to do it, long ago. Certainly

no one told her to do it for fifty-six years. She just does it.

When I telephoned Mom yesterday, I could hear my dad in the background at their house. "God knows what you've done, Libby,"

he said. "He's reserved a special place for you in Heaven."

Friday, November 11, 2005

It's My Birthday!

I am going home to Pennsylvania next Thursday to visit my mom and dad. On Saturday, while I'm at home, my Dad will celebrate

his 87th birthday.

Yesterday I called my mom. I call her almost every day. We don't talk very long, but Mom always seems really happy to talk

with me, and I love talking with her. I treasure our daily conversations. I soak up the affection in her voice,

trying to store it away for the day when it might be gone.

Each time I call Mom, I listen for signs of the Alzheimer's Disease, either in her voice or in the things she says. If

I keep the conversations brief, she seems her old self: all energy, motion, and love of life. But even in these brief conversations

the disease finds a way of slipping in.

This happened yesterday. We were talking about the weather, what she and dad were doing, how my brothers and sisters

were doing. As I do almost every day, I reminded her that I was coming up there next week. "I'll be coming up a week from

today," I said. "I can't wait."

Mom responded, "Oh, that's perfect, Freddie. You'll be here in time for my birthday!"

For a moment I was silent. It's November. Mom's birthday was on August 20th when she turned 81. The birthday next week

is Dad's, not Mom's. I was tongue-tied. What should I say?

The research on Alzheimer's Disease says that caregivers of a person with Alzheimer's are not supposed to correct

the person or argue with them, even if what they say is simply not true. First of all, it does no good. A moment after you

have successfully "corrected" the person, they will not remember what you said. Second, it agitates them and creates a downward

spiral of frustration, anxiety and sense of incompetence that aggravates the effects of memory loss.

So I bit my tongue. I shed a silent tear. And I said: "Great, Mom. I can't wait. I'm excited, too."

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Thursday, November 10, 2005

What is the Sundown Syndrome?

I visited my mom this past summer at her seashore home in Avalon, New Jersey, for her 81st birthday. While I was there I

noticed that she was fascinated with sunsets. Every night Mom made a beeline to the back dock behind the house so she could

watch the sun set over the bay.

After the sun set I noticed that mom seemed less energetic and more at loose ends. She would sit in front of the TV with

an unreadable expression on her face. Or she would get up and frantically pick things up around the house or straighten up.

Her favorite chore after dark was to adjust all the blinds on the windows. She zoomed from room to room, raising and

lowering blinds until each one was just right.

I never gave her behavior much thought until this fall I told a friend about mom's fascination with sunsets. My friend's

mom has Alzheimer's Disease, like my mom. "Oh, yes," my friend said, knowingly. "That's a common thing. It's called the Sundown

Syndrome."

Just what is the Sundown Syndrome? Here's a definition from US News & World Report's Health Report:

Sundown syndrome--also called sundowning or sunsetting--is a behavior common in people with Alzheimer's disease. It describes

the episodes of confusion, anxiety, agitation, or disorientation that often occur at dusk and into the evening hours. The

episodes may last a few hours or throughout the night.

The Sundown Syndrome can be draining for a person with Alzheimer's. The US News report offers some tips to help

caregivers cope with this problem:

As you'll see in the next article below ("What If Mom Lived in a Reminiscence Neighborhood"), assisted-living

caregivers know all about the Sundown Syndrome, and they have strategies to help their residents work around it.

For more information about the Sundown Syndrome go to About.com. Melody Conklin describes the problem she is having with her dad who has Alzheimer's, and Mary Gordon, the About.com expert,

tries to help her.

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Wednesday, November 9, 2005

What If Mom Lived in a Reminiscence Neighborhood

Yesterday I had the opportunity to talk with a representative from Sunrise Senior Living. Sunrise has three communities here in Raleigh and over 400 communities around the rest of the country. It features

assisted-living facilities for seniors with and without dementia.

(My contact chose to remain anonymous, so let's call her Susan.)

I asked Susan if Sunrise had reminiscence kits (see yesterday's blog posting). Susan said, no, but they had

memory boxes (see my blog from yesterday). They also had reminiscence neighborhoods. A reminiscence neighborhood, according to Susan, is a space set apart in a hallway or other common area in a Sunrise

community. In that space the staff of Sunrise places items that are designed to trigger a person's memory of past activities

in their life.

At least some of the Sunrise facilities have four floors. Two of the floors are for regular, assisted-living residents.

The other two floors are memory care floors for residents who have some form of dementia (including Alzheimer's Disease).

These floors are safe, secure environments and have locked doors to prevent residents from wandering off.

The reminiscence neighborhoods are set up on the memory care floors. Each neighborhood is really a "station" with

a group of items centered around a particular activity. Here are some reminiscence neighborhoods at Susan's facility:

- Mothering neighborhood -- includes a baby doll, diapers, a stroller, and baby clothing

- Office neighborhood -- includes a typewriter, a desk, and an unplugged telephone

- Sewing neighborhood -- an unplugged sewing machine (with no

needle), swaths of fabric, and spools of thread needle), swaths of fabric, and spools of thread

- Knitting neighborhood -- knitting needles, skeins of different colored yarn

- Golfing neighborhood -- golf balls, a golf bag, golf clubs

The types of neighborhoods depend on the life profile of the residents of the memory care floors at a Sunrise facility.

If a person's record shows they used to work most of their life in an office, the staff at Sunrise will assemble an office

neighborhood. Likewise, if a person played a lot of golf earlier in their life, the staff will set up a golfing neighborhood.

The types of neighborhoods are flexible and can be adapted to the profiles of the current mix of residents.

Susan said that the reminiscence neighborhoods have a powerful calming effect on the memory care residents. For example,

as the day concludes and the light fades outside the center some of the residents experience the sundowning effect (see my blog tomorrow) and become depressed or agitated. The staff notes which residents are prone to sundowning and anticipate

this problem by leading the residents to one of the reminiscence neighborhoods. According to Susan, the neighborhoods immediately

engage the resident, and as they go through the actions of activities they've done all their lives, they grow more calm and

relaxed.

According to Susan, it is important that the staff be trained to facilitate the residents' use of the reminiscence neighborhoods.

She said residents shouldn't be led to the neighborhoods and then left. It was important for the staff to play-act and orient

the resident to the activities (working at the desk, sewing, caring for the "baby," etc.) before they left the area.

"One of the biggest strengths of a Sunrise staff," she said, "is our constant training. We are trained when we begin work

at a Sunrise community. And we receive ongoing training while we work at the community."

Susan said she had two tips for anyone dealing with seniors who are suffering from dementia:

- How you talk to the person is important. Susan sees lots of relatives trying to correct their family members when they

make memory mistakes. Susan says that family members have to remember that this is an incurable disease and the memory can

not be "set straight." Relatives can't fix the person's memory, but they can agitate the person and make them even more uncomfortable

than they already are.

- It is important to use the right words. Professional caregivers stay away from words like "dementia" and "Alzheimer's

Disease" when they are talking to residents. Words such as these only increase a resident's agitation and feeling of insecurity.

Instead, for example, the staff at Sunrise might use words like "memory care" and "did you have one of your pleasant days"

when they talk with residents.

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Tuesday, November 8, 2005

Can Mementos Recapture Memories?

Reminiscence Kits are a hot item in retirement homes and communities these days. They are based, in part, on

the outreach programs organized by librarians and museum educators in the UK and Canada in the early 1990s, in which exhibits

are set up for seniors to use to reconstruct the historical context of their lives. This practice has spread to the U.S. and

has extended beyond libraries and museums to other agencies that interact with seniors. According to a US Department of Education

publication:

Reminiscence programming for older adults allows them to validate and analyze their experiences and sometimes share them

with another generation, either through direct interaction or through recording in print or on tape.

Reminiscence kits can appeal to all of a person's five senses: seeing hearing, tasting, touching, and smelling.

Examples of items that might appear in a reminiscence kit are:

Diplomas

Old scrapbooks

Photos

Jewelry

Clothing

Music

Crafts, embroidery, samplers

Pressed flowers

Pets

Sports equipment

Anything related to life accomplishments

A Life Story in a Box

Residents of the Memory Support Unit of Classic Residence by Hyatt Care Center all have

memory boxes in front of their rooms. The boxes serve to calm and relax the residents, and they act as "apartment numbers"

for the residents to identify their rooms.

They also act as "triggers" that spark residents' long-term memories.  In "There's a Story Behind Every Item in the Box," Marsha Kay Seff writes in The San Diego Union-Tribune about the memory box in front of Willma McFarlane's apartment door: In "There's a Story Behind Every Item in the Box," Marsha Kay Seff writes in The San Diego Union-Tribune about the memory box in front of Willma McFarlane's apartment door:

The pretty porcelain bride and groom in her

memory box sat atop 89-year-old Willma McFarlane's wedding cake more than 65 years ago. She was married for almost

54 years when her husband died, she says, pointing out the yellow porcelain flower that was a present from him.

"The

Haviland China plate with the red roses belonged to a one-time set of 122 dishes, painted by her mother's aunt. Most of the

them broke in 1929, when the family moved from Michigan to California and the trained lurched," according to Louise Engleman,

one of two daughters.

"You didn't ask me who that is," McFarlane says, pointing to a photo in her memory box.

"It's my senior granddaughter, my first born. She's cute . . . and smart, too."

Engleman reminds her mom,

"It's your great-granddaughter. You have four grandchildren and two great-granddaughters."

Your Life Is a Tapestry

Anything

that evokes vivid memories can appear in a memory box or reminiscence kit. The main objective is to help a senior recapture

memories from their life. According to the CNN Report "Mementos Preserve Memories:"

Your life is like a tapestry, woven from your memories of people and events. Some threads are dark, while others are bright.

Your individual tapestry shines vividly in your mind, reminding you of who you are, where you've been and what you've done. Your life is like a tapestry, woven from your memories of people and events. Some threads are dark, while others are bright.

Your individual tapestry shines vividly in your mind, reminding you of who you are, where you've been and what you've done.

Alzheimer's disease gradually robs people of the memories that make up their tapestries.

You can help mend these holes by creating a tangible repository of memories — in a scrapbook, videotape or audiotape.

Nostalgic Music and Videos Help Stimulate Memories

As part of a three-year study funded by the national Alzheimer's Association, environmental psychologist, Dr. Richard Olson, studied the responses of dementia

patients to old-time music and videos, as compared to the regular activities offered through eldercare programs. According

to Olson, the difference in the patients' reactions was "dramatic:"

"Even people who normally slept or withdrew from activities such as sewing, bingo and card games were engaged by musical selections from the '30s and '40s," said Olsen. "They would smile

and keep time with the music, sing along with the lyrics, and some even got up and danced." as sewing, bingo and card games were engaged by musical selections from the '30s and '40s," said Olsen. "They would smile

and keep time with the music, sing along with the lyrics, and some even got up and danced."

Olson said that his Musical Memory Lane project appealed to patients even in

the more advanced stages of dementia because:

Long-term memory seems to last well into the later stages, and music is often the last

stimulus to which dementia patients respond.

Can a Video Recapture Memories?

Each one of us can assemble a reminiscence kit for our parents, grandparents, and older friends.

One of the best ways to organize the kit is in the form of a life story -- a chronicle that takes the person from their birth

right up to the present. A life story validates the person and celebrates their life. In the CNN article above, the reporter

interviewed Dr. Glenn Smith, a neuropsychologist at Mayo Clinic:

"By creating a life story, you affirm for your loved one all the positive things he or she has done in life and can still

do," says Dr. Smith. "Even after your relative's memories start to fade, creating a life story shows that you value and respect

his or her legacy. It also reminds you who your loved one was before Alzheimer's disease." "By creating a life story, you affirm for your loved one all the positive things he or she has done in life and can still

do," says Dr. Smith. "Even after your relative's memories start to fade, creating a life story shows that you value and respect

his or her legacy. It also reminds you who your loved one was before Alzheimer's disease."

One of the best ways to create a life story is to use a video. All of the elements that

are in a reminiscence kit (old clothing, photos, music, scrapbooks, etc.) can be videotaped in chronological order. This process

creates a life story narrative. A person can watch all these elements come together on a TV screen. If the video also contains

interviews with members of the family and friends, then it goes beyond a reminiscence kit. Pieces of other people's memories

are also captured on the video and create the larger tapestry that makes up a person's life.

The Video Biography Project

Dr. Gene Cohen of George Washington University and the National Institute of Aging

has created a video biography project, modeled after the video biographies produced by the historian Ken Burns. Dr. Cohen created this project after his own

father became afflicted with Alzheimer's Disease.

NBC News did a TV special on one of Cohen's client families after Bessie, the mother,

was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. For six years, Bessie's son Sam watched helplessly as his mother's disease stole her away

from him. Eventually Bessie had to be moved to an institution that specializes in care for seniors with Alzheimer's

The video that Sam created gave him reason to hope. It wasn't complicated. He just took

the family's video camera and used it to record old photographs and other mementos. Still, what he came up with was a very

personal movie.

Sam didn't know what to expect. He was afraid that his mother wouldn't remember anything

on the video. He went to the Alzheimer's facility and sat down with his mother in front of the TV. The two of them, mother

and son, watched the movie together.

After the video was over, Sam was excited. "I feel like today is one of the better experiences

I've had with my Mother in months," he said. He told NBC interviewers that he planned to add new new materials to the video

and show it to his mother over and over.

Dr. Cohen is optimistic, too. He knows that video biographies cannot slow the inevitable

progress of Alzheimer's. On the other hand, the videos are valuable because "they can bring a son and a mother together once

again."

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Monday, November 7, 2005

Can I Lower My Risk of Getting Alzheimer's Disease?

In my post entitled "Can I Catch Alzheimer's from my Mom" I talked about my fears of getting Alzheimer's Disease. I dismissed

the fear of getting "infected" by my Mom. But I uncovered research that shows that children of parents with Alzheimer's Disease

are more likely to come down with Alzheimer's as they age. This is not encouraging. Is there anything I can do to lower that

risk?

Fortunately, there is. According to the research at Harvard University School of Medicine, there are seven preventive steps you can take:

- Exercise

- Keep learning

- Don't smoke

- Maintain a healthy diet

- Get a good night's sleep

- Consider taking multi-vitamins

- Cultivate close ties with others

None of these steps is a magic bullet. Even if you follow these steps you could still come down with Alzheimer's Disease.

However, each step has proven to be a factor in lowering the risk of developing Alzheimer's.

In a report entitled "Maintaining Your Memory" for ABC-TV (Chicago) Sylvia Perez writes:

The numbers are startling. More than four million Americans have Alzheimer's disease. By 2050, more than 13 million could

be living with it. But what you do today could keep you from becoming a statistic.

"I'm just a true believer. You make time for nutrition and exercise now, or you make time for disease later," said Tavis

Piattolly, nutrition expert.

Ms. Perez recommends the following steps to help you lower your risk of getting Alzheimer's:

- Exercise your brain - keep your brain active, play cards, solve puzzles, make plans, keep lists, volunteer in your church

or your community, take on challenging jobs and tasks.

- Take niacin - in a recent study people who took niacin dramatically lowered their risk of contracting Alzheimer's Disease.

(People who took 22 mg of Niacin a day lowered their risk by 80%.)

- Eat more fruits and vegetables.

- Eat more foods with B-12 vitamins, folic acid, and fish oil. (People who eat fish at least one time per week lowered their

risk by 60%.)

- Maintain your overall health, especially your blood pressure and sugar (insulin) levels.

You can get a great overview of how to "protect" your brain from the effects of Alzheimer's Disease and from aging at

Franklin Institute Online. According to a great article entitled " The Human Brain:"

The human brain is able to continually adapt and rewire itself. Even in old age, it can grow new neurons. Severe mental decline

is usually caused by disease, whereas most age-related losses in memory or motor skills simply result from inactivity and

a lack of mental exercise and stimulation. In other words, use it or lose it. The human brain is able to continually adapt and rewire itself. Even in old age, it can grow new neurons. Severe mental decline

is usually caused by disease, whereas most age-related losses in memory or motor skills simply result from inactivity and

a lack of mental exercise and stimulation. In other words, use it or lose it.

Throughout human history physical exercise was not something we chose to do (or ignore). It was a necessity.

We woke up and did hard physical labor all day long. And when we wanted to go somewhere, we walked. Walking wasn't just aerobic

exercise, it was transportation.

When my daughter Laura and I went to the Dominican Republic last year on a church medical mission, we were surprised to find

that many older people were in excellent physical and mental health. They suffered from the poor sanitary

and hygiene conditions present in a third-world country. But even 80- and 90-year-old patients at our little makeshift village

clinics were physically and mentally stronger than people the same age in the U.S. The reason? Their lives were hard, and

they ate simply. They didn't have all the food available at Wendy's, MacDonald's and well-stocked grocery stores. And they

walked everywhere and did manual labor from dawn till dusk.

I don't recommend we drop all our conveniences in the U.S. But all our labor-saving devices carry a down side

along with their benefits. The more we eat processed food and cut back on our physical and mental exercise, the more we are

prone to a physical and mental decline as we age.

Is it important to "exercise" each day like a citizen from a third-world country? Happily, no! It turns out that

we can stay physically and mentally more fit just by walking more. According to the same Franklin Institute article:

|

Studies of senior citizens who walk regularly showed significant

improvement in memory skills compared to sedentary elderly people.

Walking also improved their learning ability, concentration, and abstract

reasoning. Stroke risk was cut by 57% in people who walked as little as 20 minutes a day. |

|

|

All this research is reassuring. As our brains age it is not inevitable for them to lose brain cells and

"wither:"

Contrary to popular myth, you do not lose mass quantities of brains

cells as you get older. "There isn't much difference between a 25-year old brain and a 75-year old brain," says Dr. Monte

S. Buchsbaum, who has scanned a lot of brains as director of the Neuroscience PET Laboratory at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Cognitive decline is not inevitable. When 6,000 older people were given mental

tests throughout a ten-year period, almost 70% continued to maintain their brain power as they aged.

Certain areas of the brain, however, are more prone to damage and deterioration over time. One is the

hippocampus , which transfers new memories to long-term storage elsewhere in the brain. Another vulnerable area is the basal

ganglia, which coordinates commands to move muscles. Research indicates that mental exercise can improve these areas and positively

affect memory and physical coordination.

So for most of us, including children of parents with Alzheimer's Disease, the outlook is positive. On

the other hand, whether or not we have a family history of Alzheimer's, it helps to stay physically and mentally active and

watch what we eat. It isn't a failsafe cure for an aging brain, but it might keep us sharp longer. And we'll probably feel

better, too.

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Friday, November 4, 2005

Can I Catch Alzheimer's Disease from Mom?

On the surface this seems like a ridiculous question. All medical reports that I have read say there is no way you can

catch Alzheimer's Disease from another person, even your own mother.

On the other hand, if you are related to a person with Alzheimer's, it may increase your chances for catching the disease.

According to Info Aging:

Having a family history of Alzheimer's disease increases your risk of developing it ... Those with one parent with

the disease have a 1.5 times greater chance of developing it, and those with two afflicted parents have a 5 times higher than

average risk.

Also, as you age, your chances for Alzheimer's Disease increase:

The risk of developing Alzheimer's disease increases with increasing age up to about age 90. Researchers estimate

that as many as 50% of those over 85 have the disease.

I'm 56 years old, and I worry every day that I may be in the early stages of Alzheimer's. I am often forgetful, my short-term

memory seems to have vanished, and every time I struggle to remember someone's name, the thought occurs to me that maybe this

is an early symptom of my Alzheimer's. Or if I go down to the kitchen to get something and then can't remember what it was

I wanted, I think: Is this how it feels to have Alzheimer's? I'm 56 years old, and I worry every day that I may be in the early stages of Alzheimer's. I am often forgetful, my short-term

memory seems to have vanished, and every time I struggle to remember someone's name, the thought occurs to me that maybe this

is an early symptom of my Alzheimer's. Or if I go down to the kitchen to get something and then can't remember what it was

I wanted, I think: Is this how it feels to have Alzheimer's?

Fortunately, the Alzheimer's Association has published a helpful list of the ten warning signs for Alzheimer's:

1. Memory loss. Forgetting recently learned information is one of the most common early signs of dementia. A person

begins to forget more often and is unable to recall the information later.

What's normal? Forgetting names or appointments occasionally.

2. Difficulty performing familiar tasks. People with dementia often find it hard to plan or complete everyday tasks.

Individuals may lose track of the steps involved in preparing a meal, placing a telephone call or playing a game.

What's normal? Occasionally forgetting why you came into a room or what you planned to say.

3. Problems with language. People with Alzheimer’s disease often forget simple words or substitute unusual words,

making their speech or writing hard to understand. They may be unable to find the toothbrush, for example, and instead ask

for "that thing for my mouth.”

What's normal? Sometimes having trouble finding the right word.

4. Disorientation to time and place. People with Alzheimer’s disease can become lost in their own neighborhood,

forget where they are and how they got there, and not know how to get back home.

What's normal? Forgetting the day of the week or where you were going.

5. Poor or decreased judgment. Those with Alzheimer’s may dress inappropriately, wearing several layers on a warm

day or little clothing in the cold. They may show poor judgment, like giving away large sums of money to telemarketers.

What's normal? Making a questionable or debatable decision from time to time.

6. Problems with abstract thinking. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may have unusual difficulty performing complex

mental tasks, like forgetting what numbers are for and how they should be used.

What's normal? Finding it challenging to balance a checkbook.

7. Misplacing things. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places: an iron in the freezer

or a wristwatch in the sugar bowl.

What's normal? Misplacing keys or a wallet temporarily.

8. Changes in mood or behavior. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may show rapid mood swings – from calm to tears

to anger – for no apparent reason.

What's normal? Occasionally feeling sad or moody.

9. Changes in personality. The personalities of people with dementia can change dramatically. They may become extremely

confused, suspicious, fearful or dependent on a family member.

What's normal? People’s personalities do change somewhat with age.

10. Loss of initiative. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may become very passive, sitting in front of the TV for

hours, sleeping more than usual or not wanting to do usual activities.

What's normal? Sometimes feeling weary of work or social obligations.

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Thursday, November 3, 2005

Health Problems Accelerate Alzheimer's

My dad and my brother Owsley took my mom to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, early in the summer. They came back

and told me that the doctors at Mayo had confirmed that Mom had Alzheimer's. They also said that Mom had a clean bill of health,

except for the Alzheimer's. This felt anti-climactic, considering that the main news about Mom was bad.

As part of my research on Alzheimer's I've learned that Mom's good health outside of Alzheimer's is important in slowing

the progress of the disease. According to research reported in Look Smart:

Elderly patients with diabetes, cardiovascular disease or the apolipoprotein E e4 gene, which is linked with Alzheimer's

disease, can lose their memory up to eight times faster than their healthier counterparts, according to a report in JAMA.

Researchers suggest that exercising regularly and eating a healthful diet may help protect against short-term memory loss,

notes Psychology Today.

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

Wednesday, November 2, 2005

Memories of Mike

Two days ago I learned that my cousin Mike had died. Mike is my relative on my mom's side of the family -- the McComas

side. He is the son of my mom's brother Jack -- mom's nephew.

Mike was a loner, as far as the family was concerned. Years ago he left Kentucky where most of Mom's family still lives,

and he went out to Arizona. I got an email from him a couple years ago. He said that he was doing geneology research on the

McComas family. He asked if I had any information about the family tree. Other than that I haven't seen or talked to him in

years. The last memory I have of Mike is from fifteen years ago when he came to the McComas Family Reunion held by my sister-in-law

Teri D'Ignazio at my parents' farm in Oxford, Pennsylvania. This is a picture of Mike at that reunion.

I bring Mike up because as soon as I heard about Mike's death two days ago I tried to call my mom. I felt that Mom would

be grieving over Mike and grief-struck thinking about her brother, Jack, Mike's father.

I was unable to reach Mom until yesterday. When I finally spoke with her, the conversation didn't go as I had imagined.

I began giving my condolences, sure that Mom would be very emotional. Instead, she was totally flat. Did she know about Mike's

death? Yes, she said, she'd known for a couple days. Had she called Uncle Jack? Yes, she had spoken with him twice. "But,"

she said, "I haven't seen Mike in so long that I forget what he looks like. I haven't had any contact with him. I'm sorry

for my brother. But that's it."

This was not my mother talking. At least not the Mom that I  remembered. My mom is one of the most caring, loving, and sensitive people I know. Mike was 51 years old when he died. Mom

"knew" Mike for 51 years. Surely she had lots of memories of Mike stored away, even though she hadn't seen him in recent years.

When we were kids we used to go to Kentucky and visit Mike and his family and all of Mom's relatives. And they used to come

up north and visit us at the seashore in New Jersey. The picture here is of Mike's mother, Aunt Norma, Mom and Mike at our

shore home in Avalon, New Jersey. It is from the 1960s when Mike was around 12 or 13 years old.

I feel certain that mom's reaction to Mike's death is partly the numbness she must feel after having lost so many

dear friends in recent years who were much closer to her than Mike. But, I think, some of the lack of emotion is coming

from her Alzheimer's Disease. I looked up emotions and affect on the Internet. Here is what a leading Alzheimer's researcher, Dr. Vassilis Koliatsos at Johns Hopkins, says about Alzheimer's Disease and emotion:

It's very complicated. In fact, some people may become very emotional in the beginning, because they appreciate the changes

and they're exposed to the loss of their old selves. It's also because many of us use understanding to deal with loss. We

rationalize the loss. We have grief stages and we deal with this or that. These people don't have the ability to rationalize,

the ability to think, to abstract, and the losses and stressors and other adverse experiences of life--they become magnified

or remain unprocessed. You cannot "reason them away." In fact, you may even have hyperemotionality, increased emotionality.

Later in the disease, as the frontal lobe begins to be impaired, the emotions may become temporarily flat, until a later

stage, when the cortex is affected and the more primitive emotional centers become disinhibited. And the way that the subcortical

areas process emotion is different from the way the [cerebral] cortex processes emotion. You lose the cortical refinement,

and you become entirely subjected to more primitive types of emotional response, where silly laughter or aggression and assaultiveness

may become your mode of emotional life. It's a different type of emotional life. It's a more primitive type of emotional life,

but you don't lose your emotions.

In other words, a person doesn't lose their emotions, they just go through stages: First, intense emotions. Second,

flat emotions. Third, uninhibited "primitive" emotions.

Dr. Koliatsos' thoughts about how understanding informs our emotions may help explain what is happening to mom. According

to Koliatsos, we "know" how to be emotional when we can put what happens to us into some kind of context. In a sense,

we reason our way through our emotions and what emotion is appropriate in a given situation. Our brain figures out what kind

of emotion is right and how much emotion we should have. But if we can't place an event (like Mike's death) into any kind

of context, we're in a vacuum. We don't really have any reason to be emotional because it's the context (all the years of

knowing Mike, of knowing his family, of loving him) that's lost. Without all the memories to back it up, there is no basis

for being emotional.

I love my mom dearly. I feel terrible if she is going through any of these things. I will be visiting her soon,

in two weeks. I will see how she is doing when I get to live with her for a few days.

And there is another way of looking at this. It's a blessing, I guess, that Mom is not feeling the sense of loss

over Mike's death that I feel. She isn't feeling grief because she isn't sensitive to events like this the way she used to

be. She is in neutral. So the burden is more on those of us around her to: (1) Treat her in a loving, sensitive way, accepting

that it's okay for her to experience things this way. And: (2) Fill in the blank spot in her emotionality and take her place

in expressing grief, loss, memory and love with each other and other family members who are now going through a grieving process.

[If you liked this article, please go to my home page at Video Life Narrative where you can learn about videos you can create to honor the life of a family member or friend.]

|

|

To see earlier entries (posts) to this weblog, click on the dates above. (If there are more recent posts, you

will see a link marked "Newer.")

If you want to add us to your "blog reader" right-click on the XML tag above. Click

on "Copy Shortcut" and paste it into your blog reader under "Add Blogs."

If you like our site, please tell others about us by clicking on the envelope. Perhaps you know someone who might like

to give a Video Life Narrative as a gift to a family member or friend.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|